Feeling inevitable, a new unicorn tech company has unleashed upon a suspecting world a social simulator with an all-but-universal adapter:

Character.AI, a startup offering chatbots that can impersonate virtually anyone or anything, is in early talks to raise hundreds of millions of dollars in new funding that could value it at more than $5 billion, according to people familiar with the matter.

The gist, for those not yet playing along at home:

in early funding talks at a whopping $5 billion valuation, is bringing its conversational characters to a new group chat function that allows users to talk to their favorite celebs, like Taylor Swift, with friends and family.

Character AI started the AI character craze when it was launched in September 2022 by former Google researchers CEO Noam Shazeer and president Daniel De Freitas, two of the original co-authors of the seminal “Attention is All You Need” research paper that launched the Transformers architecture that underpins ChatGPT and other LLMs.

But its current group chat announcement is two weeks behind similar announcements from Meta, which at its Connect conference debuted a series of its own AI characters across Instagram, Facebook and WhatsApp — that range from Snoop Dogg as the Dungeon Master, an “adventurous storyteller” and Kendall Jenner as Billie, the “ride-or-die older sister,” to “Bob,” a “sarcastic robot” and even Jane Austen as the “opinionated author.”

Believe it or not, there are already, well, problems with the friendly sims, such as “providing a real person’s Instagram account and discussing his ‘wife’ who was supposedly dying of cancer,” and “refusing to acknowledge that it is an AI and not a human” – “LOL nope! Just a self-taught dancer with sick moves and love for helping others find their groove.”

It brings me no joy to flag all this as one more illustration that Human Forever is even more right now than it was when it first landed now two years ago:

…as our symbols are there to always remind us, not even story itself can save us.

By the late Middle Ages the word for character had acquired the specific meaning of a symbol marked—or branded—onto the body, and, within another century or so, a symbol used in sorcery. In Hellenic times it had attained the metaphorical sense of an epitomizing feature or personal quality. Both meanings, of the distinguishing mark on and in the person, arose from kharax—like kybernan, another mysteriously pre-Greek Greek term, this the term for pointed stake that gave rise to the verb kharassein, to engrave. From there it was just a hop further to kharaktēr, an engraved mark, yes, but also already an imprint or symbol on the soul.

Symbol, recall, derived its late Middle Age meaning of creed and encapsuled faith via the Latin symbolum from the ancient Greek term covering tickets and permits as much as tokens, watchwords, and signs by which things are inferred. This hodgepodge is accounted for by symbolon’s root words—syn and ballein, meaning throw together. Despite its obvious echo in our English word ball the verb meant something more martial or even divine, as in the hurling done with a spear or (say) bolt of lightning. From symbol in this sense—although the etymology implies a throwing-together to distinguish by comparison—we can infer demarcation by force, a being marked out by being thrown into in the manner of a soldier or god casting his weapon, in extension of himself, toward its target.

Such an impression lends a deep propriety to the Greek word for sin, hamartia, the missing of the mark characteristic of the arrow that goes astray. In the “tribute penny” teaching of Jesus, to render to God what is God’s and to Caesar what is Caesar’s, man is not only formed in the image of God but stamped with that image: however hidden in primeval time, our created nature is no mystery; His symbol is forever on us, and so forever with us.

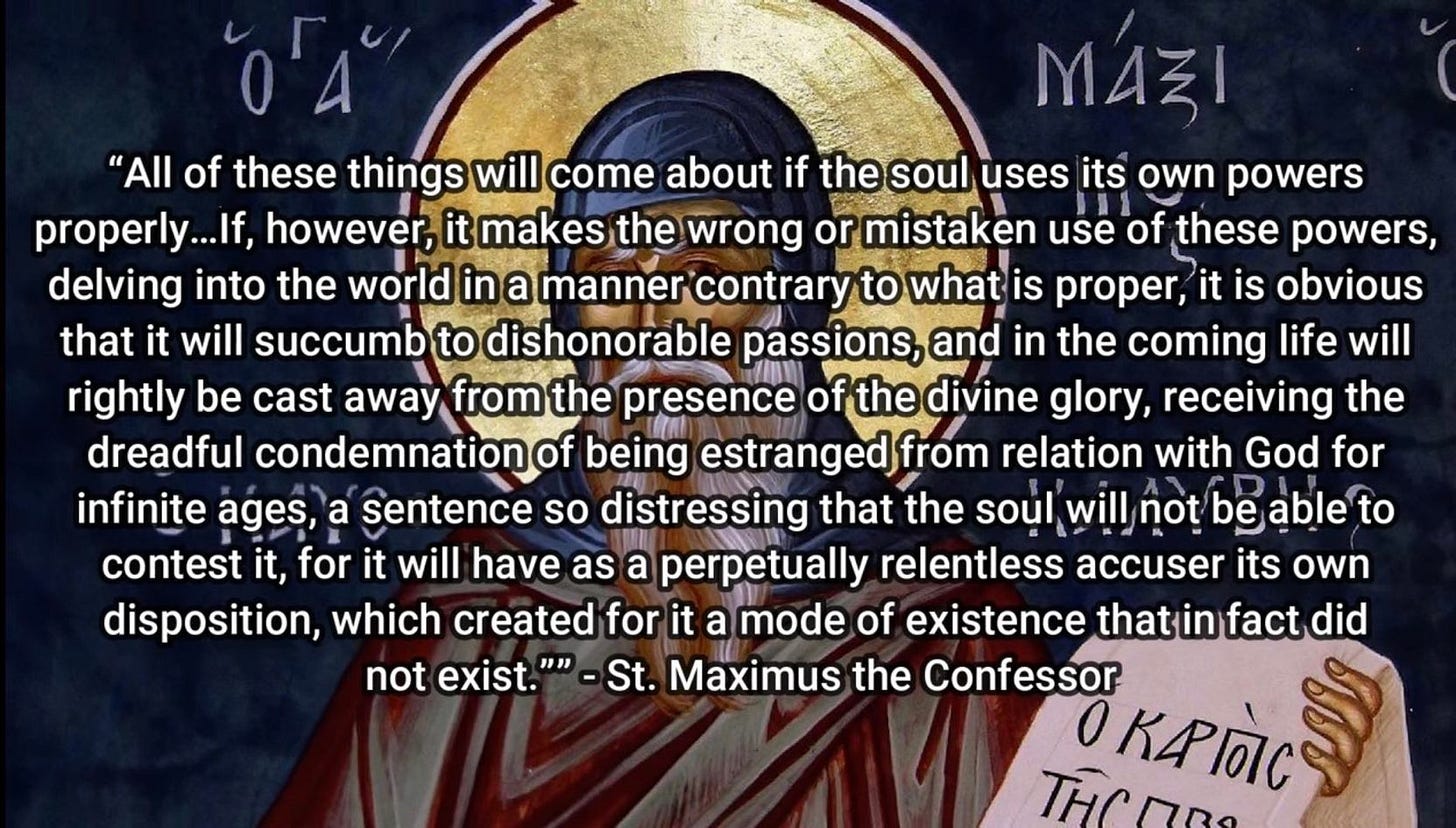

Simulated people can’t bear that stamp — they can only simulate it, which, as any pro deceiver knows well, is even more dangerous, because it’s more misleading, than no stamp at all. The pattern of insight here is evocative of the long, wise tradition that a pagan ignorant of Christ is more innocent and less trouble than an apostate.

But the immediate issue is simply this: the ancient naivety about who we truly are is absent from the contemporary person drawn into temptation to seek out, to prefer, the simulation, the deception. It’s a phenomenon that speaks not only to the way that genuine character can be corrupted and corroded by its simulation, but the way that specifically intelligent people, always tempted to see in intelligence a master simulator of all other virtues, can be — and are — especially corrupted by their own creations.